Gallery EXHIBITION

EXPERIMENTS IN THE FIELD

July 25–September 28, 2020

Adriane Colburn, Alicia Escott, Stacey Goodman, Chanell Stone, Livien Yin, Minoosh Zomorodinia, The Bureau of Linguistical Reality

Curator’s Statement by Svea Lin Soll

Artist & Curator Bios

Berkeleyside Review by Marcia Tanner: “Exhibit at Berkeley Art Center speaks to our imminent eco-catastrophe”

Read an interview with Svea Lin Soll in GIRLS Magazine

A Spectrum of Possibility in Unsettling Times

Essay by Laura EliAsieh

Some call it the apocalypse. Others the awakening. We know in our bones and increasingly in the cognitive folds of our mammalian brains that we are living through an ennobling paradox, approaching a threshold of historical progress and steadying ourselves as we experience radical shifts in social, economic, and ecological systems that are rife with injustice and death.

Ambitions to transform California’s swampy Central Valley into an agricultural paradise and the estuary of San Francisco Bay into a cosmopolitan utopia of networked liberation technology are wilting in the deadly dry heat of a climate crisis. The landscape is burning, BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) workers and families are disproportionately suffering, and digital technologies rooted in patriarchal structures threaten to distract, harass, and harvest data that targets individuals for surveillance. The artists of Experiments in the Field: Creative Collaboration in the Age of Ecological Concern at the Berkeley Art Center bear witness to this tragic and complex unfolding, and yet urge us to see the potential for regeneration of the soils, peoples, and technologies that populate this region. The meditative photographs, videos, sculptures, drawings, and linguistic provocations that comprise the exhibition, while sobering, ultimately seed hope for a world of resilience, healing, equity, inclusion, and justice.

Adriane Colburn

ADRIANE COLBURN’s work investigates the complex relationships between human infrastructure, earth systems, technology, and the natural world. Her pieces — derived from scientific data, images, and video collected through research and participation in scientific expeditions — look at how mapping is used to investigate fragile and inaccessible ecosystems. The Spoils is a multilayered matrix of elements combined to convey different aspects of the mining and global transport of raw materials and goods. An ash wood grid sits atop a selection of industrial byproducts from stone quarries, mines, and lumber mills. Capricious thrift store bric-a-brac — silver candle holders, brass figurines, and plastic toys — sits within the grid. The grid geometry references the land as seen through square aerial imagery (typical of US Geological Survey Earth Resources Observation and Science images) produced to study land change. The grid that connects everything is ash wood from a common tree in the Northeast United States that is currently being decimated by the Ash Borer beetle, a tiny insect that travels in wood pallets onboard container ships. Global circulation moves not only goods, but also critters. Reaching up from this grid-like beacon are bright spindles, deliberately painted in colors used for shipping containers and industrial use. Colburn’s correlating narrative in this work relates to the devastating effects of the global circulation of materials. The grids, lines, and spindles are abstractions of the systems that support these material industries — pipelines, ship tracks, roads, routes, and overlays.

Artist Talk with Curator Svea Lin Soll and Adriane Colburn

Chanell Stone

CHANELL STONE’s practice is invested in challenging insular views of Blackness by expanding on narratives subject to Black erasure. This avidity has led her to explore the re-naturing of the Black body to the American landscape. Fueled by the conflicting lineage surrounding African-American legacy and nature, Chanell is inspired to create work that highlights this longstanding connection to the land. Specificity is placed on urbanized African-Americans living in dense cities and the disconnection from nature that often inherently follows this lifestyle. She analyzes the Black body’s presence within urban “forests” as an effort to reclaim and reconnect to nature itself, even within the confines of the man-made environment. Through a compilation of environmental portraits, Stone explores the notion of “holding space” within one’s environment and the nuances of compartmentalized nature. Through the use of black and white analogue photography, she aims to expand the canon of traditional photography.

Artist talk with Curator Svea Lin Soll and Chanell Stone

Livien Yin

LIVIEN YIN’s sculptural weaving Bombyx Papaver is named after the Linnaean biological classification for the silkworm and the opium poppy flower. It is made from materials once traded for Chinese silk – cotton from the Americas, wool from Europe, and poppy seeds, which signify the opium imported by Britain to solve their chronic trade imbalance with China. In reference to the migration of laborers who produced these trade goods, the sculpture’s weavings draw from silk spools along the edges. This piece is from a series of sculptural renovations that refer to the histories of colonial botany, labor, and exploitation. Based on the Wardian case, a nineteenth-century container used to transport plants overseas (designed by London physician Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward), these pieces are painstakingly deliberate examinations of a troubled history. The British East India Company famously sent botanist Robert Fortune to smuggle 20,000 tea plants from China into plantations in India using Wardian cases. The early terrariums sought to hermetically seal their specimens, yet they often arrived at the dock with unexpected pests in tow. In the spirit of one of the species inadvertently transported — the traveling fungus Serpula Lacrymans — the sculpture invites fissures through these vessels of colonial conquest.

Artist talk with Curator Svea Lin Soll and Livien Lin

minoosh zomorodinia

MINOOSH ZOMORODINIA’s work is deeply informed by her cultural background, religion, and politics. Borrowing from ritual and nature, and sometimes infusing humor, she investigates ideas of self, particularly in respect to the environment. She uses installation and video to document distinct moments of time spent within each space, and to reflect her emotional, psychological, and subconscious experiences inspired by nature. In Persian culture, and around the world, city parks and gardens have been places of respite and reflection, to relax and commune. “Qanat” is a Persian word describing the ancient system of underground tunnels in the Middle East. Qanats were important factors that determined where people lived. Zomorodinia’s installation (of the same name) imagines the future of urban gardens devoid of water. The video projection was recorded in Tehran, Iran, in 2017 during a visit when Zomorodina saw rapid growth in the city as high-rise buildings took over public garden spaces. She also noticed how the qanats were destroyed due to drought. Zomorodinia takes this idea, a very real and critical issue in climate change, and brings it almost to an absurd conclusion. Yet if we look at the cumulative effects of urbanism on the destruction of local ecosystems, native plants, and animal life, this dystopian view is not so absurd. This futuristic “garden” not-so-quietly alludes to the “perils of progress,” but also asks: What will these spaces of respite be like with declining natural resources? Where is the limit to imposed industrial infrastructure? Environmental rehabilitation, if only for upgraded water systems in urban centers, is crucial to the health of our urban social landscapes.

Artist talk with Curator Svea Lin Soll and Minoosh zomorodinia

Stacey goodman

Drones have the ability to provide a top-down overview of our planet, and while associated with the military and surveillance, they also have been used in environmental management by scientists and non-governmental organizations to track animals and the health of flora in relatively non-invasive ways. The point-of-view of drones is that of Western constructs of both God and Science. STACEY GOODMAN’s interest in drone technology is haunted by these associations, by both the privilege and the power that the technology implies. He is always anxious when he flies his drone, worried that it will get damaged, violate protected airspace, or invade the privacy of those on the ground. Like map-making in the age of European exploration of the Earth, or Michel Foucault’s ruminations on the panopticon, we’ve become aware that being able to see the big picture can give one a sense of total control, both real and imagined. In the age of climate change, we are often confronted with large-scale infographics, data-driven maps, and imagery taken from above. However, our understanding of these crises through information graphics is missing the complexity and mystery that more subjective experiences provide. Goodman believes that subjective experiences of nature give us a way to assuage the panic when facing our new ecological reality, and see the beauty and mystery that data-driven infographics do not provide.

Artist talk with Curator Svea Lin Soll and Stacey Goodman

ALICIA ESCOTT

ALICIA ESCOTT’s installation of sculptural explorations dialogue with both the man-made gallery and the surrounding ecology, as it is and as it was. Her process includes research, connectivity, interwovenness/messy tangles, and disruption. This work incorporates her latest research on fire resilience and carbon sequestration in the California landscape, with ongoing investigations into the mediated ways non-human life inhabits both physical space and our psyches. Pulling directly from the coastal live oak and redwood ecology surrounding the Berkeley Art Center, she interweaves natural materials with the found detritus of contemporary human life: iPhone chargers, earbuds, gold jewelry, copper telephone wires. She references the historical California Gold Rush that settled the area (while effectively destroying the land), and the more contemporary technological “Gold Rush” that has imposed a building boom on our habitat. Wires dangle and branches reach, both seeking to transmit needed power. Acorns tenuously “sprout” from dead branches. Small pieces of plastic from construction material used to wrap buildings for renovation lay helplessly amidst natural growth. Two forlorn grizzly paws, drawn from online images of a Gold Rush–era taxidermied grizzly, reference Grizzly Peak, a summit in the Berkeley Hills (named for the California grizzly bear that inhabited the local area until the late 1800s). These symbols serve as a powerful critique of the ways humans conflate associations of flora and fauna with new functions.

Artist talk with Curator Svea Lin Soll and alicia escott

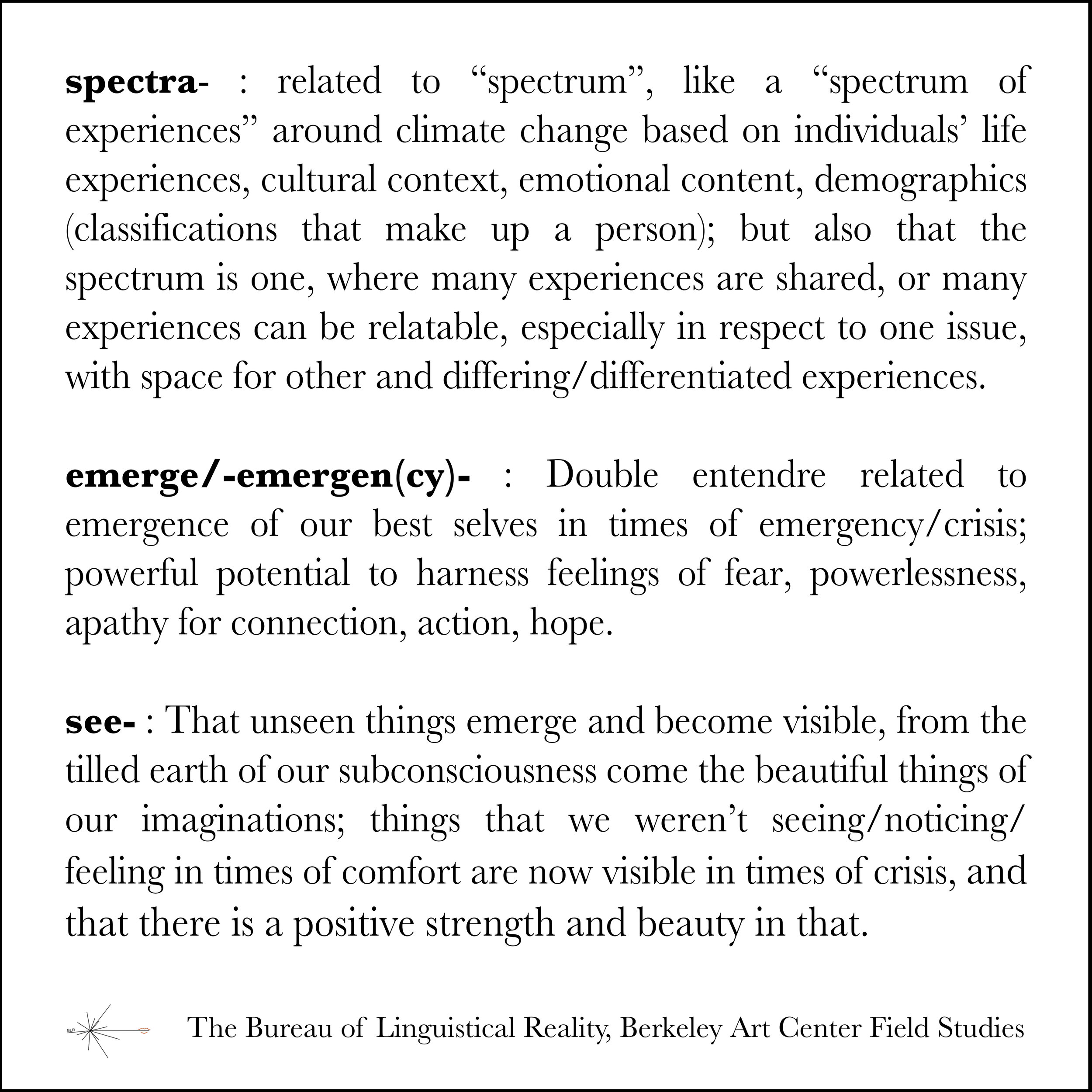

The Bureau of Linguistical Reality

THE BUREAU OF LINGUISTICAL REALITY (BLR) is a participatory artwork by artists Alicia Escott and Heidi Quante working with the public to recognize a collective loss for words to describe the emotions and experiences our species is having as our climate changes. On February 21, 2020, the artists in this show and members of the BAC community were brought together to participate in a conversation facilitated by BLR to coin a new word for an unnamed feeling or experience related to climate change and the themes of the show. Uncannily in hindsight, the group coalesced around a word describing the sense of community and camaraderie that can spring from a natural disaster. These were the early days of COVID-19, and while the novel coronavirus came up peripherally, the focus was on other climate-related disasters such as fire and flooding. Over the months since this conversation took place, we have seen the essence of what the group was trying to describe, both in its horrors and the possibilities such events can sometimes give birth to, at play on multiple levels. For this show, BLR printed the word and its definition on signs that were installed in BAC’s backyard sculpture patio.

All photos by Felix Quintana unless otherwise noted